UPDATE 5/25/24

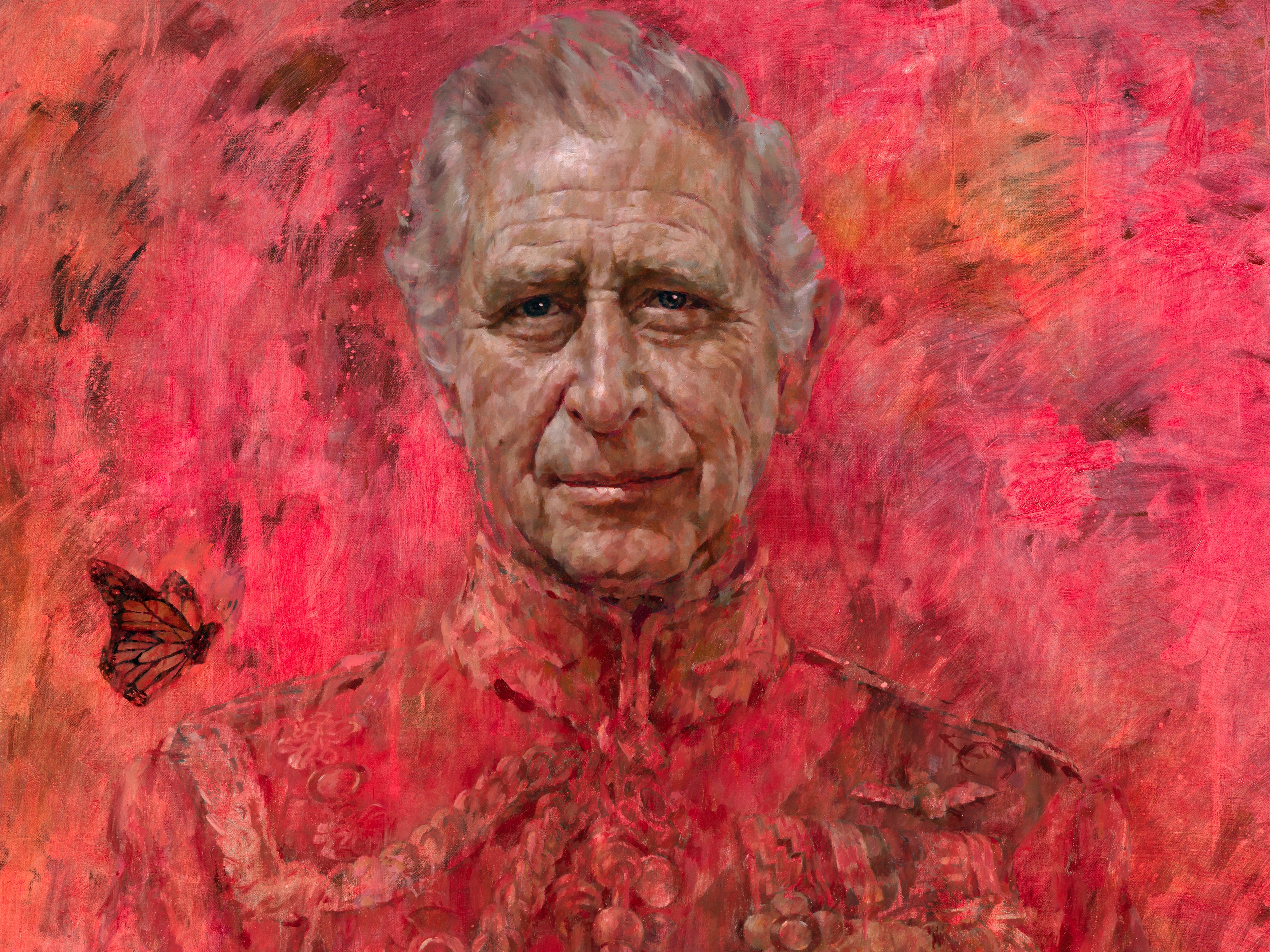

Well, King Charles has a new portrait and it is pretty scary! Of course everyone is denying any foul intent or symbolism. However, bear in mind that there are evil forces at work. Whether any of the human parties involved intentionally played a role in the creation of this piece is irrelevant. We must look beyond the obvious and reveal what is hidden. You cannot just deny the symbolism or the responses the imagery invokes.

Use your sense of discernment and your cognitive thinking. Set your skepticism aside and consider all the points addressed in the following articles and videos. There are many more you can find online. Over a Hundred. I have selected what I consider to be a good sampling.

UPDATE 5/25/24

As you study the painting, you become acutely aware that the head of the King seems to be disconnected.

Many people consider King Charles as a candidate for the personification of the Anti-Christ. It is quite possible and so I had to wonder what could the imagery in this painting be symbolizing, especially the awareness that his head seems to be floating, not really connected to his body.

The image seems sinister and foreboding. It is quite unnerving and almost horrific. It certainly invokes fear in many who view it.

I looked into the meaning and symbolism of a floating head.

\\

\\

HEAD: THE CELTIC HEAD CULT

Head-hunting as a proof of prowess and the veneration of the head as the seat of the soul and the source of spiritual potency are both far older than the dawn of the historical period. In Europe there is fairly clear evidence for them as far back as Mesolithic times. They were therefore part of the European heritage long before the Celts emerged as a distinct cultural entity. But here, as in so many other instances, what the Celts borrowed or inherited from others they soon made peculiarly their own. The veneration of the head became a central element of their ideology, a deep-set preoccupation which lasted from the birth of the Celtic peoples to their final conquest, one which left its imprint ubiquitously on their art and on their mythology.

The archaeological and artistic evidence for the head cult among the Celts is too extensive to catalog briefly. For example, at the Celto-Ligurian sanctuary of Entremont in southern Gaul (Provence), fifteen male skulls were found, several of them still bearing the marks of the spikes with which they had been fixed for display, and at Bredon Hill in Gloucestershire, England, a row of skulls uncovered near the entrance seem to have fallen from above the gate of the fort. At Entremont there are many examples of severed heads sculpted on blocks of stone, while Roquepertuse, also in Provence, has its famous decorated portico with niches in which human skulls were placed. There is also a wealth of heads sculpted in stone or carved in metal which, while not explicitly identified as severed heads, reflect clearly and sometimes very dramatically the importance accorded the head as a symbol of extraordinary power and divinity: for example, those from Heidelberg or from Mšecké-Žehrovice in Bohemia, or the pear-shaped heads on the Pfalzfeld Pillar, or the three-faced head from Corleck, County Cavan, Ireland.

Classical authors confirm the archaeological testimony. According to Posidonius, as reported by Diodorus Siculus (5.29.4–5) and Strabo (4.4.5), the Celts returned from battle with the heads of their defeated enemies hanging from the necks of their horses. The heads of their most distinguished opponents they embalmed in cedar oil and stored carefully in a chest to be displayed proudly to their visitors, and in some instances they used the skull of a distinguished enemy as a vessel for sacred libations. These and other similar references are supported by the insular Celtic literatures, where the return of the hero carrying the heads of his foes as trophies is commonplace. Cormac’s Glossary, which dates from around 900 ce, defines the term mesradh Machae, “the nut harvest of Macha (the war goddess),” as “the heads of men after they have been cut down.”

But the cult of the head went far beyond the pursuit of martial glory. The head was not only a prized heroic trophy but also a profoundly religious symbol, sometimes evidently representative of a deity and generally suggestive of supernatural wisdom and power. It was a source of prosperity, fertility, and healing as well as an apotropaic agent to ward off evil from the individual and from the community as a whole. Severed heads are often associated with sacred wells—themselves instruments of healing—in the archaeological record, in the early insular literature, and in modern oral tradition, and this association was carried over into the legends of the Christian saints. There are many instances in the literature of heads continuing to live—speaking, directing, entertaining—long after they have been separated from the body. Perhaps the most striking example is that of Bendigeidvran (Brân the Blessed), whose head presided over the otherworld and protected the island of Britain since its burial at the White Mount in London. Indeed so widespread and so persistent is the image of the head in its various aspects that Anne Ross has seen fit to describe it as “the most typical Celtic religious symbol.”

end of update

spacer

Below are some of Jonathan Yeo’s other portraits. You can see a pattern. One must wonder if he was chosen for the red background. Some say the King seemed surprised. But, was he?