In my research on the CoronaVirus I discovered some very interesting connections between the Virus, the Pangolin and THE HUNT. If you have not seen that article, I suggest you look at it before you continue. You can find it HERE:

COVID 19 – PANGOLIN CONNECTION – THE ELITE & THE HUNT

The information that I found left me curious and wanting to learn more. The Lord lead me down a deep hole. I found so much information I could not possibly address it in one article. SO, sadly, this has to be a series. I know it is hard to get people to stay with a series and complete it. I hope you will not drop off before the end. I apologize for the time it will consume, but the information is worth the investment.

Just for the record, rather than write what I believe, which really means nothing to you. I prefer to post a collection of items that reveal and/or support what I believe. It is better that you see it from multiple sources and documented. Seeing is believing so I like to provide visuals as much as possible, including videos. I appreciate the hard work that my sources have put into their presentations and I pray that you will visit their sites and support them, if you can. I always provide links. It is my desire to present enough information to lead you to THE TRUTH.

You may wonder why you would need to know all this stuff. Believe me it is very relevant to what is happening in our world today. The more you know, the better prepared you will be. God’s Word says that in the last days, men’s hearts will fail them for FEAR of what is coming on the EARTH. I believe that is because they are caught unaware. But, God’s Word says that those who belong to Him should not be UNAWARE… Because He never does anything without first revealing it to his prophets. Now, I am certainly not a prophet of GOD. But, I am a witness! And HE speaks to me. I am sharing with you, what I hear from HIM. You do with it what you like. I suggest you to go to HIM and HEAR for yourself.

Anyway… here is where I was lead and what I learned.

Please make note of the etymology of the word HUNT and meaning of the root terms.

Etymology of the word HUNT

The word hunt serves as both a noun (“to be on a hunt”) and a verb. The noun has been dated to the early 12th century, “act of chasing game,” from the verb hunt. Old English had huntung, huntoþ. The meaning of “a body of persons associated for the purpose of hunting with a pack of hounds” is first recorded in the 1570s. Meaning “the act of searching for someone or something” is from about 1600.

The verb, Old English huntian “to chase game” (transitive and intransitive), perhaps developed from hunta “hunter,” is related to hentan “to seize,” from Proto-Germanic huntojan (the source also of Gothic hinþan “to seize, capture,” Old High German hunda “booty“), which is of uncertain origin. The general sense of “search diligently” (for anything) is first recorded c. 1200.[18]

spacer

To help us to rightly understand and discern the nature of the hunting practices and rituals we need to have a better understand of RELIGION. So, let us get a clear definition of what constitutes Religion/Religious practices.

spacer

Religion, human beings’ relation to that which they regard as holy, sacred, absolute, spiritual, divine, or worthy of especial reverence. It is also commonly regarded as consisting of the way people deal with ultimate concerns about their lives and their fate after death. In many traditions, this relation and these concerns are expressed in terms of one’s relationship with or attitude toward gods or spirits; in more humanistic or naturalistic forms of religion, they are expressed in terms of one’s relationship with or attitudes toward the broader human community or the natural world. In many religions, texts are deemed to have scriptural status, and people are esteemed to be invested with spiritual or moral authority. Believers and worshippers participate in and are often enjoined to perform devotional or contemplative practices such as prayer, meditation, or particular rituals. Worship, moral conduct, right belief, and participation in religious institutions are among the constituent elements of the religious life.

spacer

Let us do the same with RITUAL.

spacer

Rituals: Definition, Types & Challenges

Now we will delve into the some of the various Rituals related to “The HUNT”.

Hunting and Cultivation Rituals

Pp. 83-94 (12) / John Alan Cohan/ Abstract

Primitive cultures have a striking relationship with animals, and remarkable rituals associated with hunting. Animals not only provide meat, but also hides and fur, and bones for fashioning into artifacts and ceremonial objects. Two broad areas of hunting rituals are one pertaining to “bribing” or coaxing animals to present themselves to the hunters; and the other involves appeasing the spirits of the animals once they have been slain. When animals are hunted, they are usually treated in a distinctive, reverent manner, partly to propitiate the ghosts of the animals, so as not to be harmed by them. Many cultures also show great respect to plants grown for food: In Papua New Guinea, for example, yams, a major food staple, are carefully attended to, and people talk to a yam as if it were human. The practice of reciting magical spells on traps, in order to attract game, is practiced in many cultures. In numerous cultures, ceremonies take place in preparation for the whaling season, including ceremonial launching of the boats, singing of whaling songs, donning of new clothes, and performing a ritual of “spearing” the woman whom they designated to represent a whale. Bears seem to be more venerated than any other hunted animal in the world. Elaborate ceremonies surround bear hunting. Bears have high intelligence, they walk in a human-like manner, they sit down against a tree with their paws, like arms, at their sides and perhaps one leg drawn up under their body. They exhibit a wide range of emotions that are very humanlike. The Nivkh people celebrate the Bear Festival, which involves a ritual sacrifice of a bear to was to commemorate deceased ancestors, or on special occasions. In the disposal of the bear’s remains, there is great respect accorded the bones, which are ceremoniously and carefully buried intact in proper position. The Motu in Papua New Guinea treat tuna with great reverence, and have elaborate preparations for the fishing season, including fasting, ritual bathing, singing, and dancing. They bless the fish before killing them. If a tuna is accidentally knocked against the side of the canoe, the fisherman must go down on his knees and kiss the fish; otherwise no more will enter the nets that day. Cattle and other livestock are treated with reverence in India, Northeast Africa, and other regions. Native Americans in the North Pacific have revitalized the First Salmon Ceremony, an aboriginal “first fruits” ritual, involving elaborate preparation and ceremonies to welcome the salmon. Protocols carefully prescribe the manner of fishing, cooking, eating, and disposal of fish bones. Reindeer breeders in Siberia practice a communal reindeer sacrifice in order to insure food, happiness, health and prosperity.

Affiliation: Western State Law School USA

spacer

From the legend of St. Hubertus, patron saint of hunters: “wildlife must not be just hunted, but equally important is the conservation and understanding of the importance of wildlife in nature and based on this, the restraint of one’s passion.”

I am hunter. I grew up in a hunting family. Most of my childhood was spent in the forest with my grandfather and father, the most important people in my life as a hunter. They taught me how to behave in nature and respect wildlife, and how important old hunting traditions are for us all.

How did hunting and associated traditions develop in Europe? The community of hunters in most European countries consider hunting not only a hobby, but also a lifestyle and mission. For most of them, it is not just about the joy of the quarry, the kill, or the trophies; it is about the honor of being hunters. It is an honor to belong to a group of people associated with nature and its resources. Is there a simple answer to the question “Does hunting make us human”? No, but the answer can be found in European hunting traditions and in the way of life that hunters lead.

Hunters in Europe and around the world struggle daily with the media and especially with many non-hunters, particularly about whether their hobby and style of obtaining food is ethically and socially acceptable. So, what is more human: a) hunting deer in the woods in such a way that it does not feel threatened before the shot is fired, or b) breeding animals solely for meat and in often appalling conditions? This is a question that we hunters are asked on a daily basis by those who claim to be guardians of nature and of animals. Many of them have no idea what the role of hunters is in the forest and what tasks they need to carry out in hunting areas throughout the year in order to be hunters. It is mostly hunters who call for the protection of endangered species, and equally it is often they who deserve credit for wildlife conservation.

An example of this is in my home country, Slovakia, where, after two world wars the state of wildlife was alarming. At that time, there were no conservationists, and the credit for the increasing game populations went to the hunters, who were already a well-organized group. Thanks to their excellent monitoring and sustainable wildlife management, it was possible for hunters to stop the decrease in game populations and, in fact, to increase their numbers.

Urbanization puts a great deal of pressure on the whole area of Central Europe. Wildlife here is under constant stress from increasing human populations and expanding industries and infrastructures. Throughout the area, there are only a few small patches of untouched nature. Today, therefore, the sustainable management of hunting is so important, and the respect for hunting traditions provides a bond between hunters and the landscape. This bond is preserved through the rituals and traditions associated with hunting.

The preservation of old hunting traditions

starts with what is known as the “communion.”This communion is the first of all hunters’ moral and ethical promises to behave, with utmost respect, towards wildlife and nature. The basis of European hunting traditions and rituals is the respect towards wildlife and to the game that is caught. This “respect” is an important part of the hunter’s life throughout the year, not just during the hunting season. Hunters manifest this respect in many places and manners: in nature, in the forest, through hunting, on social occasions, and also in their personal life. The sustainable use of wildlife and sustainable hunting management take place in the majority of European countries. Deer in the wild feel the stress of civilization. Hunters in Europe are amongst those best able to alleviate the pressures that are placed on wildlife. The reward for hunters is the opportunity to spend time in nature and to hunt. In turn, hunters also show the proper respect for wild game.

The clothing worn by European hunters when out hunting is also important. Even clothes used for working in nature are always green. For driven hunts, hunters are often dressed in uniform, and it is considered impolite to come wearing dirty boots or to be late. Driven hunts provide an opportunity for friendly gatherings, with all activities being announced by horn blowers and other hunting signals.After a hunt, whether an individual or driven hunt, hunters pay their respects to the game taken. During the closing ceremony—the game bag—the game is laid down, with its right side facing the ground, in a rectangle defined by pine branches. There are fires at each of the four corners. With this presentation, hunters say goodbye to the game and show their appreciation for nature. Each downed animal has a small branch most often from a pine tree, in its mouth representing its last bite.When taking the game from the place where it was caught, the hunters point the animal’s head toward the natural area so that for the last time it can look at the place where it lived.

Women play a very important role in European hunting nowadays. In the past, women participated mainly in the activities that followed the hunt. In the countries of former Austro–Hungary, women participated in the social activities of hunting. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, hunting in Europe underwent a final development, and so-called “exclusive hunting” was transformed into a professional activity focused on breeding and the quality and comprehensive care for game animals.

Today, as more and more women work in positions and choose hobbies that were previously dominated by men, the number of active female hunters is constantly growing. In Austria, for example, there are more than 11,000 registered female hunters. Hunting is traditionally widespread in rural areas, and women in Austria increasingly hunt and participate in public hunting life. The number of registered huntresses in Eastern European countries is also increasing annually, although their activities are connected to events organized mainly by men. The Nordic countries, too, are well known for their high numbers of hunters per capita. For example, there are more than 15,000 registered woman hunters in Sweden.

Women also occupy an important place in falconry and hunting cynology, faring well in competitions and serving as judges of various dog events and field shows.

In addition, women are active in many areas related to hunting: education, work with children and with youth, shooting, and fashion. In the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, women regularly organize workshops—to which both men and women are invited—focused on processing and cooking wild game. They exchange recipes and host culinary competitions. Women help convey the elegance of hunting and inspire men to take greater care of their garments and uniforms. Some young women become hunters even without any such family tradition, often thanks to their partners.

When speaking about hunting traditions, one of the most important sustainable hunting organizations, which has its headquarters in Europe, is the International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation (CIC). The CIC is a politically independent advisory body that aims to preserve wildlife through sustainable hunting. The CIC advocates for the sustainable use of wildlife resources and promotes, on global scale, sustainable hunting as a tool for conservation, while building on valued traditions.

spacer

Hunting Law and Ritual in Medieval English Literature

William Perry Marvin

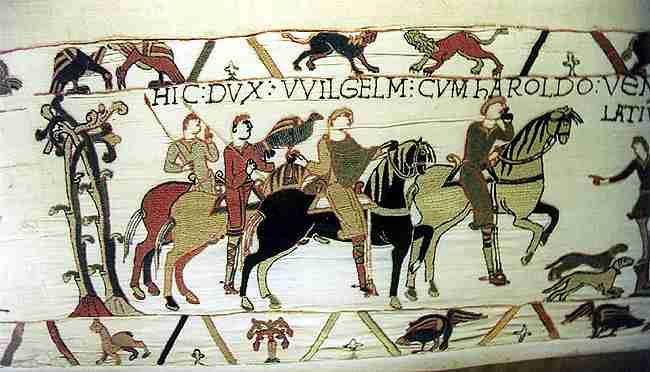

When the Normans brought the forest law to England, they ruptured centuries-old continuity in hunting culture. Never before had the right to hunt been monopolized on such a scale, nor had the arts of hunting borne such an air of strict elitism. In the hunting reserves that kings later condescended to charter to their subjects, the English cultivated a particular vocabulary and style of hunting, adding it to the canon of performative skills which contributed to chivalric identity. The reading of animal tracks had always made the function of literacy in the hunt overt; now jargon and refinements in the art of slaughter gave nuance to the hunt’s social literacy and lent it to elaborate adaptation.

spacer

Forest laws in England and Normandy in the twelfth century

One of the oldest ideas about the Norman conquest is that William the Conqueror introduced into England from Normandy the legal concept of ‘foresta’, land where hunting and the environment in which it took place were protected by draconian laws. The laws were not imposed on a blank canvas, and a combination of different factors, such as earlier extensive royal hunting rights, the king’s will, the application of forest law to land ‘outside’ that organized in manors and assessed for geld, and the status of escheated land as temporary royal demesne, all worked towards a great expansion of the afforested area. In England a great deal of non‐royal demesne was under forest law, whereas in Normandy ducal forests were broadly speaking ducal demesne. In England the competing interests of royal sport and revenue and those of the political elite combined with population pressure to make the forests a toxic political issue in a way not paralleled in Normandy.

What Is the Wild Hunt?

Across Central, Western and Northern Europe, the Wild Hunt is a well-known folk myth of a ghostly leader and his group of hunters and hounds flying through the cold night sky, accompanied by the sounds of the howling wind. The supernatural hunters are recounted as either the dead, elves, or in some instances, fairies. In the Northern tradition, the Wild Hunt was synonymous with great winter storms or changes of season.

Source

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, one of the oldest sources of Anglo-Saxon history, first mention the Wild Hunt in 1127 AD. In 1673, Johannes Scheffer, in his book Lapponia, recounts stories by the Laplanders or Sami people of the Wild Hunt. (Belgium) Author Hélène Adeline Guerber wrote of Odin and his steed, Sleipnir, in her 1895 works, Myths of the Northern Lands. She tells her readers of the souls of the dead being carried off on the stormy winds of the hunt.

The concept was popularized by author and mythologist Jacob Grimm in 1835 in his works Deutsche Mythologie. In his version of the story he mixed folklore with textual evidence from the Medieval up to the Early Modern period. Many criticized his methods, which emphasized the dynamic nature of folklore. He believed the myth to have pre-Christian roots and its leader to allegedly be based on the legends of Odin, on the darker side of his character. He also thought the leader of the hunt may have been a woman, perhaps a heathen goddess named Berchta or Holda. He believed the female may also have been Odin’s wife.

The Legend

The hunt was said to pass through the forests in the coldest, stormiest time of the year. Anyone found outdoors at the time would be swept up into the hunting party involuntarily and dropped miles from their original location. Practitioners of magic may have sought to join the berserkers in spirit, while their bodies remained safely at home. Grimm postulated the story inevitably changed from pre-Christian to more modern times. The myth originally began as a hunt led by a god and goddess visiting the land during a holy holiday, bringing blessings, and accepting offerings from people. They could be heard by the people in the howling winds, but later became known as a pack of ghouls with malicious intent.

The Leader of the Hunt

The numerous variations of the legend mention different leaders of the hunting party. In Germany the leader is known by various names, for instance, Holt, Holle, Berta, Foste or Heme. Yet one figure frequently appears in the majority of versions: Odin (also called Woden). Odin is known by two particular names which relate to the time of year the Wild Hunt was alleged to occur, Jólnir and Jauloherra. Both of these roughly mean Master of Yule, a festival celebrating the change of the seasons.

The legend of the hunt has been adapted over the years and, depending also on the geographical location, the leader of the hunt along with it. In the middle ages, with heathen deities becoming a thing of the past, the hero of the story became characters such as: Charlemagne, King Arthur or Frederick Barbarossa (the Holy Roman Emperor in the 12th century).

In the 16th century, Hans von Hackelnberg was said to lead the Wild Hunt. The story recounts him slaying a boar, accidently piercing his foot on the boar’s tusk and poisoning himself. The wound was fatal and, upon his death, von Hackelnberg declared he didn’t want to go to heaven, but instead continue with his treasured avocation – hunting. He was then forced to do this for an eternity in the night sky, or, as recounted in alternate versions, condemned to lead the Wild Hunt. Sources cite his name as possibly being a corruption of an epithet of Odin’s name.

In Wales, a variation of the story exists purporting the leader to be Gwynn ap Nudd or Lord of the Dead. In this version, the Lord of the Dead is followed by a pack of hounds with blood-red ears. In England, the same white hounds with red ears appear in legends. They were called the Gabriel hounds and said to portend doom if you saw them. Herne the Hunter, or Herlathing, is alleged to be the hunt’s leader in Southern England and possibly connected to the mythical king Herla. The Orkney Island tradition speaks of fairies or ghosts coming out at night and galloping on white horses. In Northern France, Mesnée d’Hellequin, the Goddess of Death, was said to lead the ghostly procession.

Regional Versions

Clerics in 12th century Britain reportedly witnessed the Wild Hunt. They claimed there were 20 to 30 hunters in the party and the hunt continued for nine weeks. The earlier reports available of the Wild Hunt generally represented the participants as diabolical, whereas, in later medieval retellings, the hunters became fairies instead. The legend’s origin, some believe, may be related to the Dandy Dogs. In the tale, Dando wanted a drink of water, cursed his huntsman for not having any and was then offered water by a stranger. The stranger stole Dando’s game and Dando himself, causing his dogs to give chase. Another version focuses on King Herla who had just visited the Fairy King. The king was told not to dismount his horse until the greyhound he carried had jumped down first. Three centuries passed and his men continued to ride as the dog had not jumped down yet.

In Germany, the hunter is sometimes associated with a devil or dragon and rides a horse, accompanied by numerous hounds. The prey, if mentioned, is usually a young woman who is either innocent, or guilty of some crime. Often the tail recounts someone encountering the hunt. If they oppose or stand up to the evil horde they are punished, but if they aid the hunters they are rewarded, customarily with money or the leg of a slain animal. Unfortunately, if they receive the latter, it is usually cursed and impossible to get rid of without the aid of a magician or priest. The tales also mention that someone standing in the middle of the road is somehow safe from the hunting procession.

The Wild Hunt was not seen – only heard – in Scandinavian versions of the myth. Typically the barking of Odin’s dogs, as well as the forest growing deathly silent, warned people of their imminent arrival. The hunt commonly signified a change in seasons or the onset of war in their folklore.

In Scotland, the Wild Hunt is closely linked to the fairy world in some sources. Evil fairies, or fey, were said to be cast from the Sluagh or Unseelie Court, the noble fairy court. The Sluagh allegedly flew in from the west in order to capture dying souls, resulting in people in Scotland, up until the 20th century even, closing windows and doors on the west side of their houses when they had a sick person inside! Similarly, The Orkney Islands were said to be home to trows, or trolls. The creatures supposedly hated the sunlight and tried to catch and eat mortals, unless the humans were lucky enough to escape by crossing over a stream!

In Modern Paganism

In modern Pagan tradition, practitioners incorporate the concept of the Wild Hunt in their rituals. In the late 1990s, anthropologist Susan Greenwood witnessed such a ritual. She reported the Pagans used the myth in order to lose themselves, as well as confront and restore harmony with the wild, dark side of nature. According to the Handbook of Contemporary Paganism, the hunt embraces the participation with souls, the dead and animals, as well as the ritualized circle of life and death.

Folklore sought to bring understanding to what was unexplainable at the time, often through the personification of concepts. In today’s world, we have science and technology to demystify any concepts which haven’t been categorized, cataloged, or clarified. Thankfully, we have not unlocked every puzzle in the universe yet, and with recent technological advancements, may yet go where no man has gone before!

spacer

reverence in British English – (ˈrɛvərəns ) – NOUN

VERB

5. (transitive)

venerate – transitive verb

-·at·ed, -·at·ing

Origin of venerate

from Classical Latin veneratus, past participle of venerari, to worship, reverence from venus (gen. veneris), love: see Venus

Hunting’s post-kill rituals aren’t spontaneous gestures like high-fives or war-whoops, but perhaps that’s where they began.

Maybe those instinctive, visceral celebrations evolved as ancient hunters and their tribes considered what they gained at the animal’s expense. From there, things got complicated as time and culture took hunters’ thoughts and hunting’s utilitarian tasks, and shaped them into formal tributes to the animal’s life and the meat it provided.

That process created ceremonies—large and small, personal and communal—to instill and sustain ancient reverence. Maybe that’s why post-kill hollering, laughing and chest-thumping can appear disrespectful to others. Ignoring post-kill tributes—even those silent and subtle—suggests we’ve forgotten the old ways, never took time to learn them, or never knew of them in the first place.

Either way, today’s post-kill rituals are rooted in history and traditions, and mostly of European or Native American origins. The Germans, for instance, prayed to St. Hubert, the patron saint of hunters. They built forest chapels on their hunting lands and made worship mandatory. American Indians, meanwhile, have long dropped pinches of tobacco onto the animal’s body to offer respect, believing that tobacco—crumbled or smoked—connects them to the spirit world.

Many hunters still practice post-kill rituals, borrowing from history, other cultures and their own imaginations to honor the fact that life requires death, which warrants respect. With that in mind, here are some post-kill rituals you might recognize.

Blooding: This common ritual varies widely, but usually involves a parent or the camp’s senior member taking blood from a hunter’s first kill and applying it to his or her face. Some elders carefully streak the hunter’s cheeks with a blooded finger, while others hastily smear blood all over the hunter’s face.

This rite traces back to the 700s A.D. as a tribute to St. Hubert. To receive the patron saint’s blessing for the kill, the group placed a knife in the animal’s fatal wound to coat it in blood. One of them then used the knife to gently apply red crucifixes on the hunter’s forehead and both cheeks. The hunter then accepted everyone’s congratulations. (This is the red cross of the Templar’s another pagan group)

Joe Hamilton, director of development for the Quality Deer Management Association, recalls a similar ritual from his younger days. In this case, an older hunter explained the symbolism while applying blood: The streak down the first-timer’s nose honored the quarry’s sense of smell; a second streak over one eye honored the quarry’s sense of sight; a final streak over the other eye honored the hunter’s accomplishment. “They honored the hunter for being quiet, patient and stealthy to overcome the animal’s natural defenses,” Hamilton explains.

Horn Blowing: Houndsmen hunting deer often blew horns to communicate with the dogs and each other. To make the sounds, they used everything from a bull’s actual horn sheath, to horns or bugles made of brass or pewter. Today many huntmasters in Europe still blow horns to communicate to their charges. Some American hunters do, too. Regardless where it’s blown, the sound of a horn reverberating through a hardwoods swamp or a deep forest can make the hair on hunters’ arms stand up.

The Last Bite: The “letzebissen” or “letzer bissen” is practiced in Austria, Holland and Germany, and by some Americans. Valerius Geist, 78, of British Columbia, is a retired zoology professor and hunting authority who was raised in Germany and Austria. Geist says Germans break (never cut) a twig from one of five tree species in descending preference: oak, pine, spruce, fir and alder. With the animal placed on its right side, they pull the broken twig through its mouth from one side to the other and leave it clamped between its jaws.

Eating Raw Liver: Al Hofacker, founding editor of Deer & Deer Hunting magazine, recalls hunters in 1960s-era deer camps in northeastern Wisconsin that brought the liver of their first kill back to camp each year. “At night they’d slice small pieces of the raw liver and each eat a piece,” he says.

Slitting the Throat: Hofacker also recalls a once-routine practice he could never explain. “Decades ago it was common to slit the deer’s throat before field-dressing it,” he says. “It never made sense because the heart has stopped beating, but they thought they were ‘bleeding it out.’ That’s pretty much gone now.”

Meat, Skulls, Shoulder Mounts: Long after the kill, hunters continue honoring their quarry by cherishing and consuming its meat, and displaying its skull or full-shoulder taxidermy mount. Such honors, however, are easily tarnished. “You should never desecrate head mounts by placing cigarettes in the mouths, sunglasses over the eyes, or hats or Santa Claus caps on their heads,” Geist says. “You also don’t sit on the animal’s body after you’ve killed it. That dishonors the creature.”

This is obviously an incomplete list, but perhaps it reminds us that honoring our quarry is largely a matter of the heart. And that, Geist says, should focus on the kill itself.

“Rituals aren’t a bad idea; I see their value,” Geist says. “But you show the utmost respect by concentrating on killing the animal quickly. Hunters’ conduct toward wildlife and nature should be consistent with their conduct toward other humans.”

spacer

Hunting is made of a series of rituals. Buying or being given your own hunting gun is the first one. Other Rituals begin even before the moment of the hunt itself. It starts the day before, when a man prepares his gun, when his dog starts to sense what lies ahead, when both begin to feel the excitement and tension building in their muscles; anticipation revealed in the growing charge of adrenaline filling their bodies, in the hitching of their breath.

After months of waiting, finally another adventure commences. This is the ritual of harvesting the chosen animal, then cleaning and preparing it with respect. The final ritual revolves around the company of friends – before, during, and after the hunt. These are shared moments full of storytelling and toasting to the day spent together.

• PREPARATION • PREY • SHARING • REUNION • TROPHY • RESPECT • TRADITION •

SUSPENDED MOMENT • THRILL • CONSTANT EXCITEMENT • CONCENTRATION • UNEXPECTED • ADRENALINE • CHALLENGE

|

The beauty of hunting is that it stimulates your senses. Each time you’re out on the hunt, deep in the woods, chasing the tracks of a wild animal, you are constantly refining your senses as a hunter. With every hunt, with every animal targeted and taken, you evolve as a hunter. When the day comes in which you realize that you’ve reached the same level of the wild creature before you, and you’re able to win the match of sensibilities, strength, and resilience, the feeling is indescribable. The excitement is constant, because you never know when and where it will happen exactly; it’s as if the moment itself is suspended in time, composed of a myriad of sensations, some everlasting, others ephemeral, and always leaving behind sparks to set ablaze the flame for the next match between you and the wild..

|

SHARPENING INSTINCTS • HUMAN AND ANIMAL SENSES • PRIMORDIAL INSTINCT • COMPETITION • INDIVIDUAL CHALLENGE

Hunting is a human instinct. When you go hunting, you are in competition with the animal. It’s not a matter of simply sensing the right moment or searching the right place – you have to foresee, forecast, and predict; you have to be prepared. Every one of your senses is amplified.

Thoughts on eating venison from author and F&S contributor Rick Bass.

__It’s not my place at all to suggest a right way or a wrong way. My own view is that if a post-kill ritual comes naturally, fine. But if it doesn’t, it’s as disrespectful to fake as it is to not even consider one in the first place. I don’t much like hearing other hunters whoop and shout and high-five following the occasions when they are fortunate enough to find an animal–I don’t care for that at all. But I usually hunt far enough into the backcountry that that curious aversion of mine generally takes care of itself–self-selected against such intrusion by distance and terrain.

I should hasten to say that post-kill rituals can take quite a long time to develop–years, or decades--and it’s possible also that as we age and become more attuned to our own mortality, we gain a greater interest in such matters: an increased empathy, curiosity, awareness. The ritual is partly for the animal but also partly for ourselves.

The first part of my ritual is easy; it’s what our parents told us a long time ago, the please and thank you rule. I say thank you–very quietly, under my breath really–to the mountain I’m on and to the animal. Then I set about cleaning the animal. It’s often too far from a road or trail to drag, so I quarter it for packing out. I like to leave the meat on the bone for aging–hams and shoulders–but I make sure the carcass that remains–head, vertebrae, ribs–is positioned on its side, with each part as it was, back in the brief assembly of life. I place each foreleg and shin in its appropriate pairing, so that the animal is positioned as if in midflight, reminding me of the great Edward Hoagland line about a leopard poised to jump as if in “an extra-emphatic leap into the hereafter.”

Lastly, I place my brass bullet casing against the trunk of the tree where I was sitting and position a rock over it. It’s unlikely that I’ll ever be back to that tree–there’s too much new country to hunt and too few years. But I like to think that someday, maybe a century or more from now, a hunter might be sitting against that same tree in the fall and, should he or she dislodge that oddly tilted stone–which would be lichen-covered by then and gripped with a webbing of kinnikinnick–might notice the brass and understand that once upon a time there was another hunter like him or her.

kinnikinnick – [ kin-i-kuh–nik – nouna mixture of bark, dried leaves, and sometimes tobacco, formerly smoked by the Indians and pioneers in the Ohio valley.

any of various plants used in this mixture, especially the common bearberry, Arctostaphylos uva-ursi, of the heath family.

|

Will hunters still be pursuing deer with .270-calibers, or will that traditional rifle seem by that point as quaint as stone arrowheads? I have no idea. But I like to imagine that such a hunter will stop to wonder and realize and remember that each of us is part of an ancient equation and relationship, one worthy of respect for our quarry, the landscape we hunt, and for ourselves–the manner in which we pursue our desire and our meals. Life is a privilege; the moments are almost always washing past.

KILLING ANIMALS: ON THE VIOLENCE OF SACRIFICE, THE HUNT AND THE BUTCHER

Humans are killing animals.[1] Killers of animals, they—many of them—are animals who kill. Other animals kill, of course, but no others, I suppose, carry out the killing we call sacrifice. Anthropological literature commonly treats sacrifice as a kind of exchange and an act of communication. But to grasp the kind of killing that sacrifice involves, consider its place within the set of violent acts against animals that also includes the work of hunters and butchers.

In the closing years of the twentieth century, the eastern Indonesian island of Sumba was at a tipping point as the practitioners of rituals for spirits of ancestors, commonly referred to as “marapu people,” were losing ground to an emerging Protestant majority.[2] As a young fieldworker open to any conversations going, I was privy to the suspicions, complaints, and braggadocio voiced on all sides. One of the hottest topics of polemic was animal sacrifice. Christians liked to quote a local Bible teacher: “What use are the ancestor spirits? They just use up chickens.” For their part, marapu people would point out that they only kill animals for ritual purposes, and never without an offering prayer to direct the sacrifice to its goal. By contrast, they would say, “Christians kill with no words. They are greedy, slaughtering animals whenever they feel like it, just so they can eat meat.” It’s a familiar contrast—Detienne and Vernant (1989) report ancient Greek views of meat acquisition similar to those of the marapu people. But what’s striking to me is the similarity in their moral logic, as well as what both parties do not talk about. Both focus on an instrumental logic of calculated utilities and leave mostly unmentioned both the religious logic of sacrifice, and, above all, its violence. The Christian polemic appeals to an ethics of expenditure, treating the wrongfulness of sacrifice as a matter of wasted resources.[3] For their part, marapu people stress an ethics of obligation. The ethics of obligation is all the stronger given their passionate interest in the pleasures of meat. They portray sacrifice as an elevated form of self-denial, and almost envy Christians the illicit liberty they have granted themselves to eat as they wish.[4] Like the Gentiles of the New Testament, Sumbanese Christians are distinguished by their exemption from the onerous constraints of (certain) divine laws. Indeed, so fundamentally secular is their view of meat (as opposed, say, to wafers and wine) that it could lead to the view that all killing is legal except that undertaken for sacred purposes.

Illustration by Ed Linfoot

This secular utilitarianism with regards to killing has become a largely unremarked feature of much contemporary Christianity. It was, for instance, merely part of the taken for granted background to a famous (and by 1993, unconstitutional) city ordinance in Florida, aimed at Cuban immigrants who practice Santería. The ordinance made it illegal “to unnecessarily kill, torment, torture, or mutilate an animal in a private or public ceremony not for the primary purpose of food consumption” (Palmié 1996: 184). (A literal-minded reading of this text might lead us to conclude that it’s fine to unnecessarily torture animals as long as one eats them afterwards.) (that is ridiculous! Christians do not find it acceptable to torture or abuse any one or any animal for any reason!) Although the city council was clearly motivated by anxieties of class, ethnicity, and nationality, what they chose to focus on was, presumably, that practice most readily to be abominated, the so-called “blood sacrifice.” The objection is all the more striking for this obvious point (and one that helped lead to the defeat of the measure in the courts as contravening the Constitutionally guaranteed free exercise of religion): assuming most citizens to be meat-eaters, no one was objecting to the killing of animals as such. The utilitarian logic of the butcher remains the unspoken background against which the religious stands out in marked contrast. (the bible teaches that all animals should be treated humanely and killed in the manner which causes the least trauma and really no pain, that being slicing the throat. God told man to eat meat. Christians object to sacrifice be that animal or human, because it is offensive to the one true GOD.)

The Sumbanese marapu people’s complaint suggests that one ethical objection to the reasoning offered by Christians is that instrumental meat-making denies its own violence. By contrast, sacrifice thematizes it. In this respect, the marapu people may be exemplifying a stance that runs through many traditions of sacrifice. This stance is summarized in the question posed by Veena Das, in her reflection on India’s long textual traditions of reflection on religious ritual: “can the killing of animals in sacrifice be regarded as a dramatization of everyday acts of violence that we commit simply in order to live?” (2015: 3). (NO, certainly not! Sacrifice is an act of worship. Worship of anything other than the living GOD is wrong. Whereas, taking a life so that we can live is part of the current world we live in. When we lived agricultural lives, the animal we killed to eat was usually one we had raised. It was a sacrifice in a way, but one ordained by GOD.) Although they certainly wouldn’t say this in their polemics with Christians, I suspect Sumbanese marapu people might well answer, “of course!”[5]

The pleasure of killing

You might think that hunters are those people least prone to sentimentalize the death of their prey, most likely to take a matter-of-fact attitude like that of the butcher in a big city. ‘When killing an elk or a bear, I sometimes feel that I’ve killed someone human. But one must banish such thoughts or one would go mad from shame’” (2007: 78). (Notice, by the way, the echoes of the semiosis of representation that underwrites the Durkheimian tradition: the most problematic animals are those that most resemble me, and therefore in whose place I could stand.

Sacrifice can stimulate an emotional intensification of the more general experience of the taking of life in the process of staying alive. Prayers are spoken over the sacrificial animal before the killing, in order to alert the spirits and inform the animal of the messages it should carry to the world of the dead. The killing of the animal is a means of getting the message from this material sphere to that other, immaterial one. After the killing, the response of the spirits must be sought through divinatory reading of the entrails of the victim.

(Public sacrifice of a bull) The machismo of the killer, the passion of the spectators, destruction of wealth, and the anticipation of vast quantities of tough, gamey boiled meat make this one of the highpoints of village life, persisting into the era of social media, if Sumbanese posts to Facebook are anything to go by.

What is that enthusiasm about? To start, there is a certain thrill in the sheer display of wealth and its expenditure. But many spectators also focus on the bravado of the young men who undertake the killing, and the risk at which this places them. And people seem to find the fatal blow of the machete and the struggles of the buffalo to be fascinating. On display in the plaza are physical power, domination, fear, the display of athleticism, identification with or a vast sense of distance from the victim. Sadism or empathy, risk-taking, excitement at the dramatic movements, and amusement at the occasional slapstick may all be involved.[11] Janet Hoskins (1993) points out that people in Kodi, West Sumba, often laugh at the sight of the slaughter. She says this is a nervous response to their ambivalence and, prompted by a Kodi myth about the first subjugation of cattle, suggests they are identifying with the animal but also ridiculing it for allowing them to humiliate it. In her view, the killing works in part to externalize aspects of themselves that they want to eliminate.

Then, the killing produces meat, which people anticipate with enormous relish. Sumbanese love to eat meat, but, as noted above, marapu people do so only at ceremonial feasts. These bodily pleasures are inseparable from the giving and receiving they presuppose, the commensality and reciprocity. Confronted with evidence of killing, we cannot be sure that violence is the principle focus of attention, or even fear and pain, sadism or empathy. It may also be mere excitement, in which the spectacle of killing is inseparable from the stimulation of being in a crowd – even collective effervescence – and the anticipation of the feast.

So if Sumbanese objectify themselves in the form of the sacrificial animal, they also absorb that objectified beast into themselves in the form of dead flesh. The sacrificial dialectic begins with externalization (by identifying themselves with the victim, they project certain aspects of themselves onto the animal) that makes possible, through material means, an internalization of certain aspects of the sacrifice (the flesh but not the spirit of the beast). That is, they internalize the meat that results from the killing. This is no mere representation: they are very aware of the pleasures of satiety and renewed vigor this produces. The dead body of the animal becomes part of the revitalized living body of the feasters; the animal rendered an object of human actions contributes to their constitution as subjects both through the agency by which they kill the beast and through the act of consumption by which they appropriate it to themselves. To this extent, Valeri’s concept-oriented model works well: the buffalo victim is an objectification, an externalization of an aspect of oneself. We can add that it is at the same time a subjectification of the object world, the transformation of meat into life. But we cannot eliminate from Sumbanese sacrifice the spectacle of violent killing. In the latter, however, we should not settle in advance whether the dominant key is fear, pain, prowess, sadism, domination, the thrill of the crowd, or the pleasures of the feast—indeed, all of these are in play. The category of “violence” is both too general and too narrow.

There is yet another aspect of killing to consider as well. As Valeri observed, killing dramatizes the ubiquitous experience of transformation or transition from presence to absence: “sacrificial death and destruction are also images; they represent the passage from the visible to the invisible and thereby make it possible to conceive the transformations the sacrifice is supposed to produce” (1985: 69). We might say the same of Sumbanese killing, which is meant to extend a bridge to the invisible world.[12] Sumbanese sacrificial animals convey messages between the manifest world of the living and the invisible world of the dead. In Sumba, sacrificial killing must, as noted above, always include words, and the reading of entrails. These foreground the fact that the killing is a transition between perceptible and imperceptible worlds (Keane 2008). The animal is made to die, in order to bring along with it to the world of the dead words that were spoken by humans in the world of the living, and, through the medium of entrail-reading, to convey a reply.

CONTINUE TO:

Many rituals reenact particular events from a culture or religion’s mythology. Exactly what this reenactment is intended to signify or accomplish varies greatly from culture to culture, but the structure of mythological reenactment is a common one. As noted in the previous section, most rituals take place in a sacred space, and mythological reenactments typically follow this pattern. Some mythological reenactments are intended to commemorate an event that is believed by participants to have literally taken place in this historical past. Other mythological reenactments are intended to bring participants into mystical communion with supernatural beings or distant ancestors that accomplished mythological tasks, such as creating aspects of the natural landscape or defeating some dangerous foe.

Many rituals reenact particular events from a culture or religion’s mythology. Exactly what this reenactment is intended to signify or accomplish varies greatly from culture to culture, but the structure of mythological reenactment is a common one. As noted in the previous section, most rituals take place in a sacred space, and mythological reenactments typically follow this pattern. Some mythological reenactments are intended to commemorate an event that is believed by participants to have literally taken place in this historical past. Other mythological reenactments are intended to bring participants into mystical communion with supernatural beings or distant ancestors that accomplished mythological tasks, such as creating aspects of the natural landscape or defeating some dangerous foe.